EQT review of signals on previous research: Decarbonisation

Review of signals from OC on previously generated JPM published research

Review of Prediction of overall CO2 target

China plans to make its carbon dioxide emissions peak by 2030; JPM however uses the Tsinghua Report predictions of somewhere between 2025-2030, and predicts a peak at 2025

- The JPM report 13 October 2020 argues that the government is keen to address climate change due to the impacts from heavy rains, rising sea levels, and floods. They note that a rise in the sea level is a particular concern of China as more than 800m Chinese people live along the coastal provinces and moreover the Yellow River contains around 40% of China’s population and GDP.

Official China Review:

There is a tension in looking at external studies (which are more likely to have dependable data and a less rosy view of government activity) and looking at checking China’s plans not by central decree but rather by summing up the activities and plans made by provincial actors. We recommend going through provincial plan by plan; at that level, the cracks start to emerge. The other recommendation is to match it to other plans and see which ones contradict themselves. This leads to an aggregate decomposition.

Chinese ministries and local governments have made policy plans for carbon emissions and neutrality, and we searched through those on Bilby. As the head of China’s economy puts it, despite a "tough battle", China “must ensure” it reaches peak emissions (2030) & carbon neutrality (2060) on time. Planners are scrambling to keep up. Aluminium sector bodies’ plan lists peak carbon by 2025, and to cut emissions from peak by 40% in 2040. Ministry statements say that steel production this year must decline and “to reduce steel production is an important step towards reaching peak carbon emissions and carbon neutrality”. From this perspective, we worry that there is no coordinated central signal yet. cuts to steel and coal from above will not be strong enough a signal to also reform energy, transportation, industry, construction, and agriculture. Rather, based on the outcome of pilots, it seems most likely China will put a price on carbon (JPM report April 2021 also discusses). But, and we all agree on this, the price on carbon is weak and there is no bite to it yet. So this projection appears, based on a review of the documentation through Bilby, to be an optimistic prediction.

Take for example China’s 14th Five Year Plan; the key driver and variable is China’s economic growth. Changing the amount of coal versus renewables in the plan makes little difference to the outcome, whereas altering the energy intensity target or China’s GDP growth for this year (assumed to be 6.5%) greatly alters the equation. What is missing in that is that local governments have an enormous incentive to meet a high economic growth target as they recover from COVID.

We can see this now: the first quarter of 2021 has seen CO2 emissions grow at their fastest pace for more than a decade. around 70% of the increase in emissions in the first quarter of 2021 was due to increased use of coal, with growth in oil demand contributing 20% and fossil gas demand 10%. Some 60% of the increase in coal use came from the power sector, with the metals industry (15%) and the building materials sector (10%, cement and glass) the next largest contributors.

If we do a year rolling count, the year ending March 2021 is now 600m tonnes (5%) above the total for 2019. Either way, this is not looking good for 2030, let alone 2025.

We suggest using official figures for the domestic production, import and export of fossil fuels and cement, as well as commercial data on changes in stocks of stored fuel, and matching that to the NDRC plans. This can then be matched with quick searches of the documents as listed above, and act as a cross check. It should also give early warning, albeit only by a couple of days.

Plans for future activity

JPM notes that a number of things need to be clarified in Chinese environmental reports: “The definition of carbon neutrality for China and whether it means reducing fossil fuels to zero, or to reduce them to minimal levels and offset the remaining emissions through natural absorption or carbon capture and storage; detailed reduction targets by polluting sectors including power industrials and transportations; and the medium term goal for carbon dioxide reduction and the power mix in 2025.”

JPM also foresees a potential halt in new project approvals in China's chemical industry.

Official China Review:

Agreed, we searched through the official, policy and regulatory lines and found a distinct lack of medium term goals. We think that this is of major concern. China's 2020 targets it reached with room to spare. Its next targets however, do not kick in until 2030. And carbon neutrality itself is not a goal until 2060. The Chinese system does not function on 40 year timelines. Rather, it is explicitly geared for five year plans, milestones, and targets. In the absence of these we think that progress less likely. This may be leading to the divergence we're currently seeing in the data between China's goals and what is happening as economy recovers.

All of the industries have their plans until 2035, and the local governments have their plans, and all of the other areas which actually use coal have their plans. The necessary changes would come locally at lower levels of government, but there is an incentives problem.

Local governments have many, many indicators they are judged on. This means that they need to do their own prioritisation, and that rarely factors in ideas such as environmental approvals unless they are directly ordered and can be held accountable for failing at their order. Local leaders will be held accountable should there be shortfalls or shortcomings in economic growth.

And local leaders feel like they need coal power. Energy-intensive sectors know that local leaders need their support and tax revenues and are often keen to build their own power plants. One company alone built 17.5GW of coal-fired installed capacity in 2020; there were only 11.9GW of coal-powered plants commissioned in the entire world in the same year. This is both economic stimulus package and energy need. Environmental concerns and targets will take a back seat.

(A search across the various lines of data in Bilby also noted that there are also some less savoury reasons: state-owned energy companies are often good at getting loans, and energy projects can breed graft. One story saw so much corrupt cash found in a senior regulator’s house that one-quarter of the currency counters quit their jobs due to “burn-out”.)

There are still a plethora of projects under planning or construction. As such provincial governments are already planning in purchasing coal plants in the classic prisoners dilemma problem. The only body able to stop this happening is the central government at the very top, and there have been little sign of elite focus on reducing coal usage.

This means mixed signals. China's State Council, the head of the central government, released a big directive on speeding up green and low-carbon development. Yet an examination of the Hunan province five-year plan showed that Hunan will build 12GW new Coal-fired power capacity by 2025.

A Bilby search also showed a Hunan official saying at the annual meeting of all China’s legislators that 'Hunan could see power supply shortage as large as 10GW in 2021-2025, facing pressure from emission reduction vs energy security'.

Greenhouse gas emissions

China also needs to shift from focusing on air pollution measures to instead look at greenhouse gas emissions. The ultra-low emission requirement on power plants does not currently capture carbon dioxide. JPM believes that regulators will place a much greater emphasis on carbon dioxide emissions in the upcoming 14th 5 year plan, with more incentives to promote power and carbon storage

Official China Review:

This did not come true. That is more due to a signal conflict. Air pollution measures were one of Xi Jinping’s three wars, the leader’s prerogative. Anything that Xi directly orders (ie, says should happen and is measurable) is going to happen. Greenhouse gas emissions signals on the other hand are at a more normal base level of power and authority. Suggest in this case a hierarchy of orders.

Carbon price

China's carbon price is much lower than that of other countries that have managed to bring about a price on carbon. In China carbon is RMB 36 per tonne where is in the European Union it is RMB210 per tonne.

China is trying to address this in the most recent 14th 5 year plan, with three steps: 1) working with industry associations of governing bodies to set a total emission volume standard feature industry, including call cement and steel; 2) using the agreed standard, assigning total emissions quotas which industry company; 3) using this centralised market mechanism to set up to trade carbon quotas. JPM notes that the large number of industries and even more companies involved mean that the government will have to step up its efforts.

Official China Review:

We would go further here. This method of setting things will always result in the environment not being the greatest priority. Without a central single point of accountability and an easy to measure number such as profit it is virtually impossible to coordinate all the actors. The ETS scheme has one advantage in being originally launced by the NDRC. The Ministry of Ecology and Environment is a reporting body, unable to effectively enforce measurement but good at collecting information. In May 2019 they made local governments submit lists of power plants that met the threshold for inclusion in the ETS, and released a trial plan for allocating emissions allowances. That has now been delivered on time. Yet there has been no penalties applied yet.

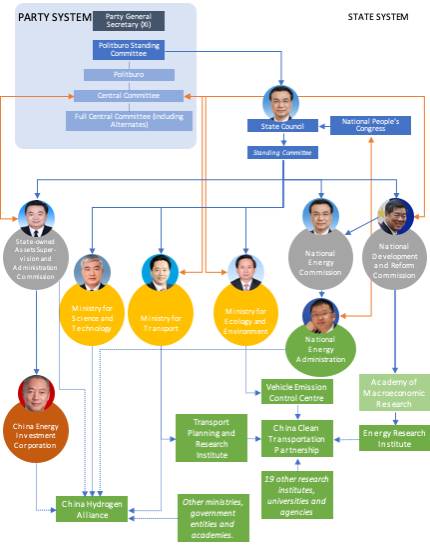

The absence of a robust national mechanism controlled by serious central regulators who are able to hold local governments accountable, and thus actually force action, remains unlikely under the current structure. It relies on inspections. The chart below shows the order of documentation, and what a coordination nightmare it is.

To make matters worse, this then affects the listing regulations. JPM notes that companies are to list all their ESG responsibilities as compulsory. That is not true. Under Chinese law, the environmental protection ministry must choose who to determine an “important national polluter” company, based on reports filed upwards from their local bureaux. Should a listed company be named and shamed, they will need to file regular public reports with the onshore stock exchange. There are also green credit and IPO regulations that make it harder for named polluters to raise monies. Indeed, the market penalties are much greater than the formal administrative punishments handed out to those who pollute. This means that there will be many games between firms and regulators as to who is termed a major polluter and who is not.

Hydrogen

China is already the world’s largest producer and user of hydrogen, and it has long supported research and development into hydrogen, fuel cells and related technologies. Our search of Bilby showed that in 2005, the Ministry of Science and Technology released a hydrogen roadmap, The Vision for Hydrogen Energy in China.

Since 2015, China has ramped up its state support and expenditure on research and development for hydrogen and fuel cells. A key driver behind this increased expenditure (and the related push to diversify its energy supply) is the strategic development of innovation-oriented manufacturing industries. However, as it has elsewhere, there has been a marked increase in attention paid to hydrogen as a future fuel source in China. For example, the number of articles reported in China’s leading professional energy industry news source, China Energy News, that contains in the title ‘hydrogen’ or a derivative of that word, spiked sharply in 2018 and increased even further in 2019 and 2020, reflecting greater interest in hydrogen and the investment, research and policy activity around it. We recommend this leading indicator search.

That said, our worry remains; a search of the many materials on hydrogen in Bilby shows that China has a plethora of plans and instruments that guide activity around the development of its hydrogen economy but it lacks a unifying strategy. This reflects the decentralised, multi-level, multi-agency nature of energy policy in China. It has strategies developed by entities such as the China Hydrogen Alliance, which focuses on industrial and technological measures to promote hydrogen. Other strategies may be developed by individual provincial governments, working groups such as the China Clean Transportation Partnership, by ministries, or more centrally, such as by the National Development and Reform Commission. While many of these strategies are impressive, and some may even be reasonably comprehensive, their overlap and short shelf-life diminish their value.

This also makes recommending one leading signal hard. We think the best is probably using SASAC (left hand side of diagram). Very large SOEs are leading on hydrogen development and that means that the state asset administrator will give early warning signals. (We wrote about one of these in the trial period already: https://bilby.ghost.io/sichuan-ailian-ltd-semiconductor/).

Bilby search: Chinese laws and instruments applicable to hydrogen and renewable energy

Instrument | Authority | Purpose | Scope | Date |

Renewable Energy Law | National People's Congress | To give priority to the development and utilization of renewable energy in energy development and to promote the establishment and development of the renewable energy market by setting an overall target for the development and utilization of renewable energy. | County-level and higher. | First adopted 2005, amended 2009. |

Five-Year Plans - various | National Development and Reform Commission | Since the 9th Five-Year Plan, funding has been allocated towards the development of China’s hydrogen sector. This is binding on local governments and they need to respond. | Central Government | 9th(1996) and onwards |

Made in China 2025 | State Council | A strategic plan aimed at transforming Chinese manufacturing to high-value, higher-technology products and services, and to directly challenge the high-tech capabilities of foreign companies. Green energy, green vehicles and power equipment are included in the target sectors. | Central Government | 2015-2025 |

Energy Saving and New Energy Vehicle Technology Roadmap | Chinese Society of Automotive Engineers | Framed around Made in China 2025, this also included a technology roadmap for China’s automotive industry around hydrogen fuel-cell vehicles, including targets for 1 million vehicles by 2030. | National | 2016 |

Hydrogen energy vision and technology roadmap | Ministry of Science and Technology | Sets out an overview of the opportunities for China arising from a hydrogen economy, examines the factors affecting the development of a hydrogen economy, presents a timeline for the accomplishment of various technical and uptake milestones leading ultimately to a transition to a commercially viable, self-sustaining industry. | Central Government | 2005 |

863 Program (also known as the State High-Tech Development Plan) | Ministry of Science and Technology | A research funding and coordination mechanism, the program was designed to stimulate the development of advanced technologies in nine technological fields, including energy. Several fuel cell and hydrogen projects were funded. | Central Government | 1986-2016 |

Program 973 (also known as the National Basic Research Program) | State Science and Education Steering Group | A research funding and coordination mechanism, the program is funded to support basic scientific research and to foster the development of new technologies aligned with national priorities. | Central Government | 1997-ongoing |

Comments ()